A Month of Kinesis in Production

We’ve been powering a production component with Kinesis for a little over a month now so it seems like as good of a time as ever to put together a few thoughts on how it’s worked out. My goal here is to put together a few short objective observations on how it’s performed, followed by what I perceive as the product’s major limitations, and then a short opinion as to whether I’d use it again. Keep in mind though that while we’re putting a bit of load on our stream, we haven’t come close to pushing the product to its limits (well, except for one limit, see below), so if you’re planning on pushing a cluster to the 100s of GBs or TBs scale, the findings here may not be sufficient to make an informed decision on the product.

First off, a little background: Kinesis is Amazon’s solution for real-time data processing that’s been designed from the get go for horizontal scalability, reliability, and low latency. It’s a data store that can have records produced into it on one end, and consumed from it on the other. This may sound a little like a queue, but it differs from a queue in that every injected event is designed to be consumed as many times as necessary, allowing many consumers to read the stream simultaneously and in isolation from each other. To achieve this, records are persistent for a period of time (currently a 24 hour sliding window) so that any individual consumers can go offline and still come back and consume the stream from where they left off.

The basic resource of Kinesis is a stream, which is a logical grouping of stream data around a single topic. To scale a stream, it can be subdivided into shards, each of which can handle 1 MB/s of data written to it and 2 MB/s of data read from it (I’d expect these numbers to change over time though, see Kinesis limits). Records injected into a stream go a shard based on a partition key chosen for each record by the user which is transformed using a hash function so that it maps to a single shard consistently. Partition keys offload scalability decisions to the Kinesis users, which is a simple way of achieving a powerful level of control over a Kinesis cluster in that they can make their own decisions around what type of record ordering is important to them.

The most obvious alternative to Kinesis is Kafka, which provides a similar model built on top of open-source Apache infrastructure. The systems differ significantly in implementation, but both aim to provide speed, scalability, and durability.

Kinesis has a well-written developer guide if you want to learn a little more about it. I’ve also written a few other articles on the subject. See Guaranteeing Order with Kinesis Bulk Puts and Kinesis Shard Splitting & Merging by Example.

Performance and stability

Probably of most paramount concern is how Kinesis performs in production. One thing to keep in mind when looking at these numbers is that Kinesis’ durability characteristic is highly relevant. When injecting a record to a stream, that record is synchronously replicated to three different availability zones in the region to help guarantee that you’ll get it out of the other side. There is a performance cost associated with this level of reliability, and comparing the numbers below to a single-node system like Redis (for example), would be nonsense.

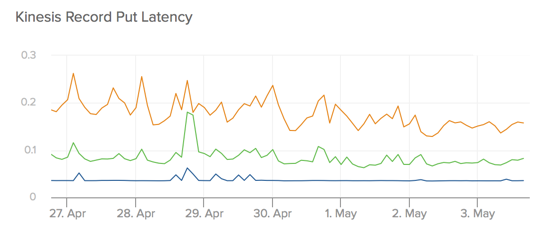

First off, we have put latency on the side of our producer. These metrics are generated from one of six different producer nodes running within the same AWS region as the Kinesis stream. All of these use the bulk put records API, and include a variable payload roughly in the range of 1 to 10 events. The Kinesis API operates over HTTP, and our code re-uses an already open connection to perform our operations whenever possible.

As seen in the chart below, P50 manages to stay right around the 35 ms mark very consistently. P95 is usually right around 100 ms and P99 closer to 200 ms, but we don’t see 300 ms broken under these metrics.

(My apologies for these charts by the way, it seems that utilitarian things like axis labels and data legends aren’t considered pretty enough by Librato to merit inclusion in a chart snapshot.)

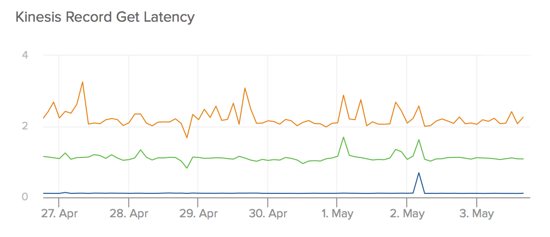

Next up: time to fetch records from a Kinesis shard. As above, these numbers are from within the same region as the Kinesis stream and are bulk operations in that the consumers will fetch as many unconsumed records as are available. Reads from a Kinesis stream seem to be a little slower than writes, and we see P50 closer to 150 ms with P95 around 1 s and P99 a little over 2 s.

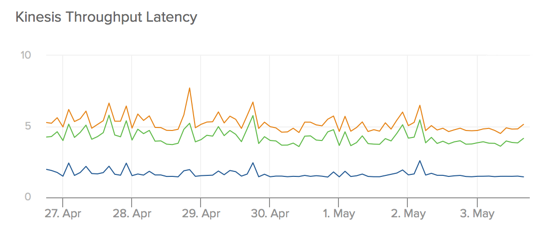

Lastly, let’s take a look at the total time that it takes a record to traverse the stream from its moment of inception on the producer to when it’s in the hands of a consumer. Note that this not a perfect number in that includes some time that the record spends in our own application as it waits to be dispatched by a background process to Kinesis, but I’ve included it anyway given that many real-world Kinesis users may have a similar mechanism in their own stacks.

P50 on this total throughput time sits right around 1.5 s, with P95 and P99 sitting a little further out around 5 s.

All-in-all, I consider these numbers pretty good for a distributed system. In our particular use case, accuracy is more important then ultra low-latency throughput, so given the durability guarantees that Kinesis is getting us here, I’m more than willing to accept them.

A little more on the qualitative side of observation, we’ve still yet to notice a serious operational problem in one of our Kinesis streams throughout the time that we’ve had them online. This doesn’t give me much data to report on how well they behave during a degraded situation like a serious outage, but also demonstrates that the infrastructure is pretty reliable.

Limitations

Now onto the part that may be the most important for the prospective Kinesis user: the product’s limitations. I’m happy to report that I didn’t find many, but those that I did find are significant.

You get five (reads)

Scalability is right there on the Kinesis front page as one of the core features of the product, and indeed it is scalable: by default a stream in US East can have up to 50 shards (this limit can be increased by opening a support ticket with AWS), each of which can handle 1 MB/s in and 2 MB/s out for a theoretically maximum of 50 MB/s in and 100 MB/s out. That’s an incredible amount of data! However, despite being very scalable along this one dimension, it scales very poorly along another: the number of consumers that a stream can have.

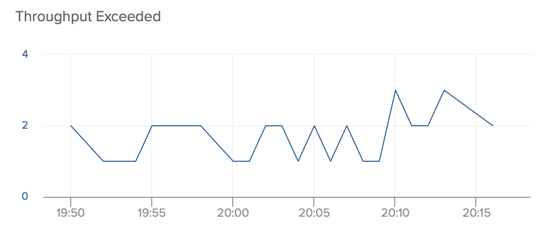

Each shard on a stream supports a maximum limit of 5 reads per second. That number is right on the limits page, but at no point does the documentation really spell out its repercussions (or at least nowhere that I could find). If each shard only supports 5 read operations, and each application consuming the stream must consume every shard, then you can only have a maximum of 5 applications if you want to read the stream once per second. If you want to have ten applications consuming the stream, then you will have to limit each so that on average it only consumes the stream once every two seconds. Each read can pull down 10 MB of data, so keeping up with the stream isn’t a problem, but you can see how you’ll have to sacrifice latency in order to scale up the number of consumers reading the stream.

This might be fine for a number of Kinesis use cases, but I was hoping to be able to build an infrastructure where I could have 100 or more applications consuming the stream. To achieve this I’d have to throttle each one back to only read on average of once every 20 seconds – a number that’s unacceptable even for my relatively latency insensitive uses.

Given that each shard already has a hard limit on input/output, I don’t completely understand why such an aggressive per-shard limit on reads is necessary, but I can speculate that whatever mechanism they’re using to perform a read is incredibly expensive. I’ve corresponded a little bit with Kinesis staff on it, but haven’t been able to get a good answer. The Rube Goldberg-esque solution of chaining streams together by piping output of one to input of another until I’ve achieved sufficient fanout to support all my consumers was suggested a couple times, but that’s a path that I wasn’t too anxious to take.

To help illustrate the problem, here’s a chart of the number of “throughput exceeded” errors stemming from the read limit that our consumers ran into just over the past 30 minutes. This is only three consumers hitting a low throughput stream once a second.

Vanishing history

As described in my previous article Kinesis Shard Splitting & Merging by Example, a Kinesis shard is immutable in the sense that if it’s split or merged, the existing shard is closed and new shards are created in its place. I find this to be quite an elegant solution to the problem of consumers trying to guarantee their read order across these events. To help consumers check that they’re appropriately consumed closed shards to completion, the DescribeStream API endpoint allows them to examine the ancestry of each currently open shard and the range of sequence numbers that every closed shard handled during its lifetime.

This is all well and good except that the list in DescribeStream is pruned on a regular basis and closed shards removed. This prevents a consumer that comes back online across a split and outside of the pruning window from determining whether it can come back online in a way that it’s certain that it consumed all of the stream’s data. No API parameter is available to request a complete list.

Removing these old records of ancestry on such an aggressive schedule to save a few hundred bytes of JSON on an infrequently made API call seems like a pretty strange design decision to me. Like with the previous problem, corresponding with staff didn’t help me gain any particular insight into its justification.

Comparison to Kafka

I don’t have a great deal of experience with Kafka (we ran a cluster for a few months but didn’t put together any kind of analysis of worthwhile depth), so I’ll keep this section short.

One aspect of Kinesis that I did appreciate is the removal of the concept of a topic, which is a channel of sorts within a Kafka cluster that allows messages to be grouped together logically. The topic is an important feature when considering the maintenance and operation of Kafka in that it allows a single cluster to be re-used for a number of applications (and therefore fewer moving parts to keep an eye on), but as a developer, this isn’t something that I really want to think about. If I want to send one type record I’ll provision a Kinesis stream for it, and if I want to send a different type of record I’ll provision a separate stream for that. From my perspective as an AWS user, those are two completely independent services that scale orthogonally and have their isolated sets of resources (rate limits, throughput capacity, and the like). As far as I’m concerned, this is a major win for hosted services.

Summary

I’m overall pretty happy with my experience with Kinesis, and we’ll continue to run services on it for the foreseeable future. In general it behaves like a perfect infrastructure component in that it performs well and stays out of the way.

By far the biggest rub for me is the 5 reads per second limit, which will certainly limit what we can do with the product. Admittedly, if I’d understood the consequences of this earlier, I probably would have pushed harder for Kafka, but it’s not worth re-implementing what we already have over.

For prospective users, I’d recommend Kinesis in most places just to help people stay out of the business of maintaining their own Kafka cluster and learning how to operate it. That said, if the read limit sounds like it may be a problem, it might be wise to investigate all possible options.

Did I make a mistake? Please consider sending a pull request.